Minyma Malilu by Carolanne Ken, 2022, acrylic on linen, 90 x 120cm

Minyma Malilu by Carolanne Ken, 2022, acrylic on linen, 90 x 120cm

Recognised as one of the oldest living cultures in the history of humankind, the Aboriginal people of Australia are believed to have inhabited the continent for as long as 80,000 years - maintaining the most ancient, unbroken tradition of artmaking in the world. A study of the origins of Aboriginal art offers invaluable insight into our innate human predispositions towards storytelling, creativity and markmaking. In the more recent, post-colonial landscape of Australian society, the Aboriginal art industry as we know it today is globally acclaimed, often considered one of the most exciting contemporary art movements of the 20th century.

With hundreds of Aboriginal language groups intersecting the continent, nurtured by the land across a vast range of climates, it is impossible to condense tens of thousands of years of culture and creativity into one brief summary. While there are commonalities between different language groups, Aboriginal art is characterised by regional diversity. Aboriginal people across the continent continue to draw from the wisdom of their ancestors who forged their coexistence with the natural landscape and the intertwined spiritual tenets of their culture, finding relevance and breathing life into the contemporary art industries of an increasingly globalised world.

Untitled by Yinarupa Nangala, 2023, acrylic on linen, 90 x 120 cm

Untitled by Yinarupa Nangala, 2023, acrylic on linen, 90 x 120 cm

EARLY ABORIGINAL ART

A core tenet of Aboriginal culture is the tradition of oral history; relying on storytelling, rather than written records, to pass on cultural knowledge to the younger generations. In this sense, lasting remains of ancient visual expressions are an invaluable source of information in understanding the prehistory of Australia. Paintings on bark, rock, and skin are some of the most widely recognised forms of expression, traditionally using ochre pigments as a paint-like medium, as well as ephemeral sand drawings. Although most likely to withstand the tests of time, rock art is a selective record - it is naturally subject to processes of erosion, limiting our access to even older art. One of the earliest known pieces of rock art with a confirmed date is a charcoal drawing, dated at 28,000 years, found at Nawarla Gabarnmang rock shelter in southwest Arnhemland. There are over 100,000 recorded rock art sites in Australia (Deep Time Dreaming, Griffiths, 2018); some famous examples include Ubirr, in the Kakadu region of the Northern territory, and the more recent Wandjina rock paintings in the Kimberleys of Western Australia.

Wandjina Rock Art on the Barnett River, Western Australia

Petroglyphs (rock engravings) from Tjoritja, East MacDonnell Ranges

Even ceremonial or practical objects, such as weapons or hunting items, occur in decorative forms - incorporating aesthetic features derived entirely from the natural environment, such as seeds, shells, feathers, bones, fixtures of beeswax, ironwood resin or spinifex gum, a variety of masterful wood-carving practices, and weavings of fibres and strings (Aboriginal Art, Morphy, 1998 pp.8). A major point of difference is found here from a Western understanding of the purpose of art - the majority of Aboriginal art is “uncollectable”. Often produced in ritual contexts - body paint being a particular example - it is intended for the artwork to be ephemeral; destroyed over the course of the ceremony, or left to disappear naturally, as fleeting and cyclical as any part of nature.

For decades following the landing of British settlers on the Australian continent in 1788, the appraisal of Aboriginal art forms by Europeans was virtually nonexistent, and often met with disinterest and denial. The early colonial ideology was ‘terra nullius’ - an empty land, “belonging to no-one”. Outlined by anthropology professor and author Howard Morphy, it was in the interests of colonialism not to see Aboriginal art, let alone acknowledge it as art - allowing for the continued appropriation of their land. As time passed, the general public gradually became more receptive to seeing the value and merit in Indigenous cultural expression. Increasing interest, activism, and changing social circumstances saw gradual political action and legislative change. Events in the art world were major influences to these shifting landscapes, and traditional art practices were increasingly used by Aboriginal people to assert their rights to both land and to cultural recognition.

My Grandmother's Country by Maureen Baker, 2021, acrylic on linen, 90 x 150 cm

My Grandmother's Country by Maureen Baker, 2021, acrylic on linen, 90 x 150 cm

ALBERT NAMATJIRA

While ochre pigments were used by Indigenous peoples for tens of thousands of years to paint on skin, bark, and rock, the first paintings completed in accordance with Western expectations and materials were the watercolours of Arrernte artist, the famed Albert (born Elea) Namatjira. Born in 1902, he began painting in the 1930s at the place of his birth, the Hermannsburg mission near Mparntwe (Alice Springs). Albert masterfully depicted the desert landscapes of his ancestral country, Tjoritja (the MacDonnell Ranges) and surrounds. Albert Namatjira’s first exhibition was held in Adelaide in 1937, and by the 1940s and -50s, his paintings had catapulted to international acclaim. Aboriginal sportsman and activist Charles Perkins considered Albert Namatjira’s rise to fame as a first point of recognition of Aboriginal peoples by broader white society In 1957, Albert became the first Aboriginal man to be granted Australian citizenship - although this did not spare him from many hurdles, particularly in regards to the discriminatory laws that prevented Aboriginal people from owning or leasing land. Albert passed away in 1959, survived by his wife, daughter, and five sons. Albert Namatjira left an incredible legacy that paved the way for future Indigenous artists; and directly influenced the establishment of the Aboriginal owned and directed Iltja Ntjarra / Many Hands Arts Centre in Mparntwe (Alice Springs) as well as the Namatjira Trust, which successfully fought for the copyright transfer of Albert’s works.

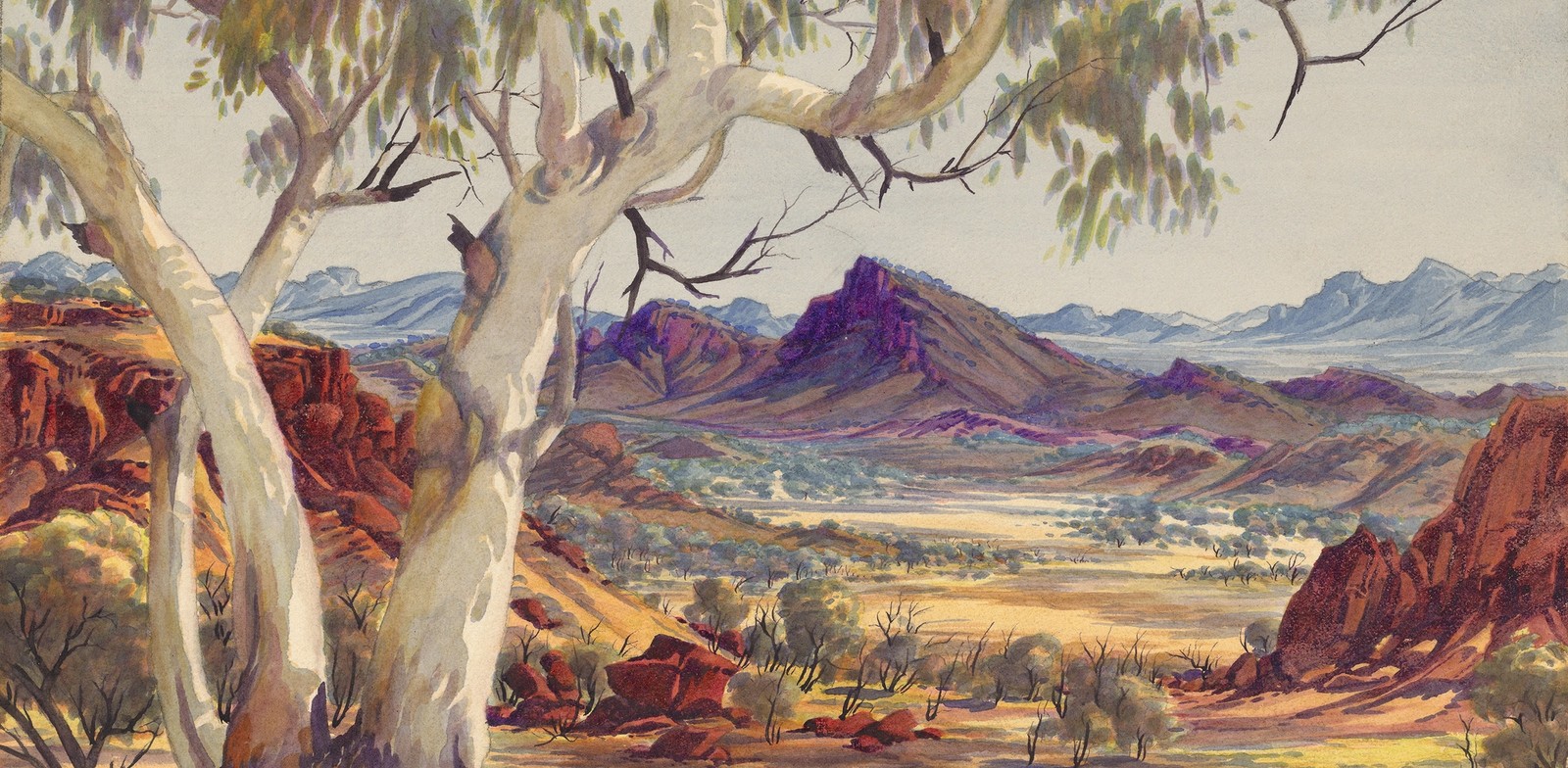

Central Australian Landscape by Albert Namatjira, c. 1955-1959, watercolour and pencil on paper

© Albert Namatjira Legacy Trust, image retrieved from Queensland Gallery of Modern Art

PAPUNYA TULA ARTISTS CO-OPERATIVE

Although Aboriginal people maintain the oldest surviving tradition of artmaking in the world, the status of the Indigenous art industry as we experience it today is remarkably youthful by comparison. The Western Desert movement, generally recognised as the genesis of the ‘contemporary’ Aboriginal art movement, dawned in the 1970s, in the remote community of Papunya in the Northern Territory, some 240 km north-west of Alice Springs. In 1971, a school teacher named Geoffrey Bardon began noticing the symbols that Aboriginal men would draw in the sand while telling stories; mapping the physical and spiritual country that was significant to them, often from an aerial point of view. Geoffrey encouraged the men to paint these symbols with more lasting mediums, providing them with canvas and board, and organising the painting of a collaborative mural. The administrators of the community were not interested in encouraging traditional practices, yet Bardon persisted - ultimately sparking an unprecedented shift in the art landscape of the time. While Albert Namatjira had depicted landscapes using techniques deemed ‘civilised’ by white consumers, this was the first time that Aboriginal people began painting their stories and topographic maps onto Western facades. Painting, as a universal language, opened up a pathway to better understanding Aboriginal culture, free from the language barriers that had caused storytelling and song traditions to be lost on Europeans. This movement is where the dotting technique began to enter the visual consciousness of broader Australian society, and today is one of the most recognised visual associations with Aboriginal art. The technique is thought to have originated as a way to protect secret and sacred knowledge from the public or those who were not possessing the appropriate levels of initiation. As more artists began emerging from communities such as Yuendumu, Balgo and Utopia, employing similar methods to communicate symbols of various stories and Dreamings, dot art came to be affirmed as one the most dominant art forms of the desert regions.

Women's Ceremony in a cave by Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, 1971, acrylic on board

© Estate of Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, image retrieved from Queensland Gallery of Modern Art

THE CONTEMPORARY INDUSTRY - CHANGING LANDSCAPES

As outlined above, the Aboriginal art industry only found its most fervent developments in the second half of the 20th century. Indeed, it wasn’t until the late 1950s that major collections were sourced and exhibited by art galleries, rather than the ethnographic museums that Aboriginal artworks had been previously limited to. The rich iconography and dynamism of artmaking practices from the far north of the continent had a significant influence on the widening reception of Aboriginal art, with galleries curating notable collections from places like Yirrkala, Melville and Bathurst Islands. The formation of the Women’s Batik Group in the Utopia homelands of the Northern Territory in 1979 also had revolutionary influence in the developments of the contemporary art movements, and as well as accelerating the developments that had dawned in the 1960s (Aboriginal Art, Morphy, 2018, pp. 248) towards an industry with a notable presence of female artists.

By the mid-1980s, the landscape of Aboriginal art was unrecognisable compared to early colonial attitudes of ignorance and dismissal. Aboriginal art was in demand, and there was an apparent desire to disseminate Indigenous iconography into the visual consciousness of Australia. Aboriginal art was commissioned for national parks and public buildings and institutions, and in 1988, a mosaic by Western Desert artist Kumantje Jagamara (also known as Michael Nelson Jagamara) was famously incorporated into the design of the new Parliament House in Canberra.

Forecourt of Parliament House; featuring a mosaic based on a painting by Kumantje Jagamara, 'Possum and Wallaby Dreaming', 1985.

In the span of just a few decades, the industry had shifted from a local to global frame. Fast forward to the highly lucrative industry of the 21st century, May 2007 saw the first Aboriginal artwork to achieve over $1million at auction - a painting titled ‘Earth’s Creation’ by famed Anmatyerre artist, the late Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Emily was not just the first Indigenous artist, but also the first female Australian artist to reach over a million dollars at auction.

Earth’s Creation by Emily Kame Kngwarreye, 1994, synthetic polymer paint on linen mounted on canvas, four panels, each 275 x 160 cm

© Emily Kame Kngwarreye; image retrieved from the National Museum of Australia

Aboriginal art provides a lens through which we can peer into some of the earliest visual expressions of human history; it resonates deeply within cultural and social landscapes due to its inherent connection to land and collective identity. It provides an opportunity to expand our understanding of the continent and its traditional custodians, reflecting the artistic and anthropological wisdoms of an ancient culture. Imbued with tens of thousands of years of unbroken ritual maintenance, Aboriginal art functions in much the same manner as their oral history - keeping the past alive, paying homage to the spirit of the land and to the ancestral creators, while maintaining infinite relevance to the present moment. An examination of the oldest, unbroken tradition of artmaking carries us to here, now - where we can bear witness to the assertion of Indigenous cultural identity on a global scale, continuing to enthral contemporary art industries and individuals of all backgrounds with the authority of a visual language as ancient, enduring and evolving as Country itself.